What to do about rising costs when your rooftop honey already sells for $25 a jar

The makers of artisanal packaged consumer products can’t pass along higher prices as easily as big companies. But many are finding creative solutions.

Andrew Coté of Andrew’s Honey at the Union Square Farmers Market. Photo: Nina Roberts

Published on The Business of Business on December 14, 2021

Dolcezza is an Argentine-inspired gelato company making dense, creamy flavors like Stracciatella and Mascarpone and Berries. Co-founders Violeta Edelman and Robb Duncan (yes, they did meet years ago at an ayahuasca retreat in Brazil) are keeping their pints, available nationally at Whole Foods, among other markets, and Dolcezza’s own e-commerce site, priced at $6.99.

“We don't want that price to go up,” says Duncan, calling it the “sweet spot.” Edelman, originally from Buenos Aires, adds, “It’s super important for us to be accessible,” as distribution is limited for pints costing $8, $9 or more. So, rather than raise prices to offset rising costs, from ingredients to packaging, they’re focusing on scaling up their supermarket flavor selection. “In the meantime,” Edelman says, “we’re absorbing costs.”

The consumer goods industry—including small packaged goods ranging from ice cream and biscuits, to pastas and jarred sauces, manufactured by multinational giants and artisanal producers alike—has been shaken to its core since Covid hit. Pandemic-induced shutdowns and labor shortages have thrown a proverbial monkey wrench into the supply chain, gumming up production at factories; causing backups at distribution centers, warehouses and ports.

U.S. consumers could face price increases for the next 12 to 18 months due to supply chain issues and labor shortages, according to Phil Lempert, a supermarket consultant based in Los Angeles, California. The rate of inflation in the US surged to 6.8% in November 2021, according to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the fastest rise in prices over a year since 1982.

But while multinational conglomerates can simply pass along higher costs to shoppers (with varying degrees of pushback), makers of small artisanal products face a more complicated predicament. Most are already selling goods at relatively high price points in their categories, relying on high-quality ingredients and small batch manufacturing. Losing customers by raising prices even more could be devastating.

Fortunately, most small consumer goods companies have been able to avoid price hikes by finding creative solutions. And, so far, it’s been working out for them. According to Boston Consulting Group, small and extra-small consumer goods companies had revenue gains of 15.4% to 18.3% over 2020, while midsize and large companies had 7.5% to 9.5% revenue increases.

“I'll raise prices as soon as I absolutely need to,” Andrew Coté, of Andrew’s Local Honey in New York City, told us. “I'm not going to do it opportunistically.”

Dolcezza’s Mascarpone & Berries, sourced from local farms. Photo: Nina Roberts

But that doesn’t mean opportunities can’t find smaller producers. Dolcezza, the specialty ice cream maker, launched its packaged pints in 2019, more than a decade after its initial start as a brick and mortar gelateria in the greater Washington DC area, where it’s still based. “We had no idea how important it was to launch with Whole Foods,” Duncan said, adding that the timing proved to be fortuitous given the impending pandemic. “It was incredible to have the grocery, when the brick and mortar was so challenged.”

Dolcezza has had “no hiccups whatsoever,” as Duncan puts it, as it sources its usual ingredients from local farms. Milk is supplied by Roam Dairy in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, commandeered by Omar Beiler, who Duncan likes to call his “Amish brother.” Strawberries hail from Agriberry in Hanover, Virginia, and other ingredients are also from local suppliers.

Grocery consultant Lempert thinks a company like Dolcezza, which manufactures its own product, is in better shape to weather inflation and a broken supply chain than companies using a third party, known as a co-packer, to manufacture. “Those, I worry about,” says Lempert, as co-packers produce for multiple brands in the same facility, and larger companies’ huge orders might squeeze out the smaller brands’ production needs.

Meanwhile, Coté, the honey producer, did in fact raise prices on two honey products by 6% a few months ago, matching the rate of inflation. But he noted that he felt the products were underpriced, and it was his first price increase in five or six years.

Coté sells honey collected from hives atop buildings across New York City in areas like the Bronx and Rockaway Beach for $25 per 8 ounce jar. His non-rooftop honeys range from $10 to $15 a jar.

Talking to us on a Saturday morning in New York’s Union Square, where he was carefully arranging his honey jars amid a frenzy of shoppers, Coté explained that he avoids the pinch of inflation by purchasing supplies in “great bulk.”

But Coté nonetheless found himself on what was perhaps the receiving end of an inflation-fueled rage. A buyer at Stew Leonard’s, a specialty food market chain in Connecticut that’s carried Andrew’s Local Honey for years, wanted Coté’s honey at a reduced price. “Their buyer wanted me to lower my price by another 33%,” Coté recalls. “I don't mind somebody asking, but when I tell them I'm not able to do it because it's below my actual cost,” says Coté, who posted the testy text exchange on Instagram, “I don't need to be swore at and insulted. So, I'm happy to not do business with people like that.”

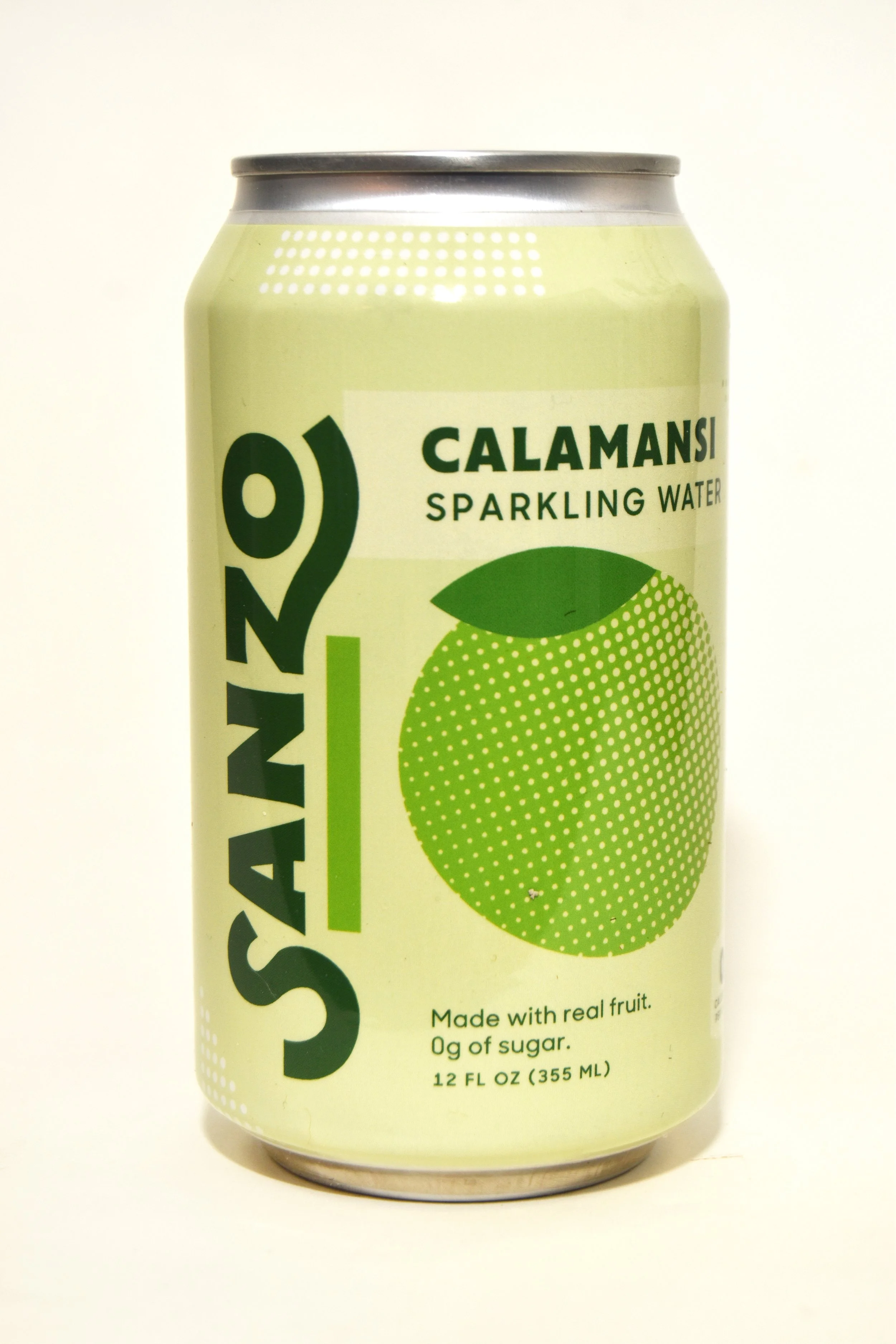

Sanzo, based in Queens, New York. Photo: Nina Roberts

Another company trying to avoid raising prices is Sanzo, a New York City based beverage company making sparkling water flavored with lychee, mango or calamansi, a lime from the Philippines, where founder Sandro Roco’s parents were born. It’s sold through e-commerce and chains like Erewhon and Whole Foods. Sanzo is manufactured in Pennsylvania and freight costs have risen more than 700% in some instances, according to Roco, but he’s keeping a can priced at $2.69.

Freight increases are not uncommon for small manufacturers, in part due to a shortage of truck drivers. Lempert thinks that one piece of the supply chain puzzle going forward will be to decentralize warehousing and manufacturing. “Instead of that one huge factory, we might have 20 or 30, smaller factories dotted throughout the country,” says Lempert, so manufacturers and suppliers are less reliant on long haul trucking.

New use of a nationwide warehousing network is what Evy Chen, the founder of Evy Tea, based in Boston, Massachusetts, is relying on as she shifts her cold brew tea company to primarily e-commerce from food services. Chen, originally from Fujian, China, ripped apart every aspect of her ten-year-old company over the past year and half, and relaunched last month. “From an emotional perspective,” Chen reflects, “it was almost like, you know, Evy pre-Covid had to die.”

In addition to “Evy Palmer,” Evy Tea features flavors like hibiscus, green tea and Keemun black tea with berries. A 12 ounce can of Evy Tea now costs $3.49, up from the previous 16 ounce bottle priced at $2.99, but Chen says, “We didn't ‘raise prices’ from my perspective.” Chen points out that selling a container load at a time versus several cans at a time, is a very different model for margin requirements. “We really had to rewire that and build in the correct margin to support infrastructure along the way,” she says.

Madhu Chocolate co-founders Harshit Gupta and Elliot Curelop. Photo: Nina Roberts

Harshit Gupta, the co-founder of Madhu Chocolate, based in Austin, Texas, makes artisanal chocolate bars in flavors inspired by his native India, like Masala Chai, Cardamon and Idukki Black Pepper. Insulated shipping boxes have almost doubled in cost, according to Gupta, and cacao from Kerala, India, used in one bar, has had a 45%price hike.

When costs began to increase, Gupta and co-founder Elliott Curelop discussed a $0.50 price hike. “We might start losing customers,” Gupta recalls thinking, so for now, Madhu Chocolate’s prices remain at $9 a bar via e-commerce (with the exception of one bar selling for $10). “Obviously, we don't want to turn our customers off,” says Gupta, “which is not something we can afford at this time.”

However next year, Gupta foresees an increase in pricing. “Because the fact of the matter is that all the businesses, which we rely on, are increasing prices,” states Gupta. When Madhu Chocolate does raise its prices, Gupta and Curelop plan to have costs documented for customers to see, in the name of transparency.

“It’s a good time to support small businesses,” says Kevin Chanthasiriphan, the cofounder of Immi, a new, VC-backed instant ramen company based in the Bay Area, “to some degree, all the multinationals raising their prices, brings us closer to parity.”

Chanthasiriphan, who goes by KChan, not to be confused with Immi’s other co-founder, Kevin Lee (they’re sometimes referred to as “The Kevins”) says that because Immi launched during the pandemic, “issues around freight and logistics were already baked into our modeling.”

Immi’s ramen, which contains more than double the protein than mainstream brands like Cup Noodles or Maruchan, and less sodium, has in fact been able to lower their prices to about $6 to $6.50 depending on order size since launching. (It’s not quiteramen parity, as a package of Maruchan costs about $0.25, but consumers do have a healthier ramen option.)

“The average consumer had no idea what ‘supply chain’ meant before this,” says Lempert of the term. It’s now found in multiple headlines a day and even a recent newyorker.com cartoon by Jason Katzenstein featuring Cookie Monster concerned about cookie availability.

“Prices are going to continue to go up and not level off in 12 months,” warns Lempert, if the food supply chain is not completely reimagined. Even if Covid gets eradicated, Lempert says the US can’t go back to previous supply methods, like trucking lettuce across the country for example, which he calls, “ridiculous,” and paying workers a non-living wage. “We realized how broken the supply chain was,” says Lempert of the pandemic, “and it's not one simple thing that we can point to, ‘That's going to fix it.’” He adds that anybody who thinks that, “doesn't understand the complexity of our food supply.”